Guest post by Norman Mogil

When two of the biggest US pension funds reported very disappointing financial results this month, it became apparent that the pension industry needs a reality check. For the past fiscal year, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System earned a merger return of 0.6 percent on its investments; the California State Teachers' Retirement System did only marginally better, clocking an investment return of 1.4 percent. Both funds had a target rate of return 7.5 percent. To be fair, one year's result does not make a trend, but the results were so far below target as to warrant an examination of the new world confronting pension fund managers.

Underfunding of Public and Private Funds

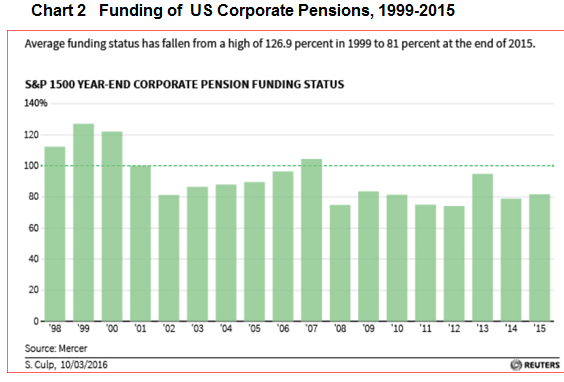

We begin by taking the measure of how far public pension funds (Chart 1) and corporate pension funds (Chart 2) are underfunded. Underfunding is a moving target over time and is reflective of several moving parts, such as shifts in demographics (an aging population), estimates of the longevity of retirees, economic performance (slow growth means lower contributions), and rates of return on various asset classes. In the US, both public and private pensions have experienced a steady erosion in funding status over the past decade and a half. The large public pension plans and large corporations only support 75-80 percent of liabilities today. The underfunding exists despite a very good rate of growth in total assets under management; however, liabilities have increased faster and one reason for this can be traced to the dramatic fall in long-term interest, especially, post 2008.

The decline in interest rates affects both sides of the ledger. On the asset side, lower interest rates imply lower overall returns; on the liability side, the book value of pension obligations move up due to the lower discount rate used to calculation the liabilities. In fact, these two changes in value—assets and liabilities—do not offset one another, rather they move in the same direction. The net effect is that the underfunding situation is exacerbated, increasing the gap between assets and liabilities. More worrisome is that pension funds will have to replace higher-yielding bonds with lower-yielding bonds over time. This concern is especially acute in the UK, Germany, and other EU countries as bonds yield sink into negative territory, thereby reducing the size of the bond market in which pensions can participate. The tightening of the supply of positive-yielding bonds is becoming a very real problem today, let alone in the coming years.

Must-read: How a Public Pension Crisis Is Driving an Epic Credit Boom

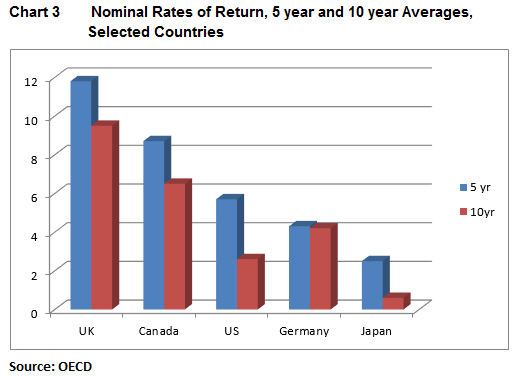

Overall rates of return earned in the pension industry throughout the developed world have steadily fallen, resulting in a relatively weak performance in asset accumulation. A recent OECD study measured the rates of return over 5-year and 10-year periods (Chart 3). Nominally, the US (at 3 percent) has underperformed its peer group in the UK (at 9 percent) and Canada (at 6 percent); all countries have experienced weak results over a 10-year period. These relatively low rates of return are at the heart of the issue facing the industry: namely, are the targets set too high?

What Does It Take to Earn 7.5%?

The vast majority of the US pension industry clings to investment targets of 7-8 percent annually. True, this is an expectation over an average of 5 years as the industry must live in a world of high volatility. Yet, how realistic is this target? Let's look at it from a macroeconomic perspective. A nominal return of 7.5 percent implies that national income—wages and profits—should, on average, grow at 7.5 percent. That is, the national income growth should be about 5 percent real growth plus 2.5 percent inflation. Neither that real growth rate or that inflation rate has been achieved on a sustained basis over the past decade. Moreover, mainstream economists do not anticipate that the US economy will achieve real growth rates of 5 percent in the coming years; continued moderate real growth of 2-3 percent is anticipated; and inflation expectations remain very subdued, as evidenced by the low long-term interest rates. So, from a macro perspective, the 7.5 percent target is hard to justify. The industry needs to generate rates of return well in excess of the economy′s capacity to create income growth.

Read Here's Why All Pension Funds Are Doomed, Doomed, Doomed

Considering the target from a microeconomic perspective seems even more elusive. Table 1A presents the findings of the OECD study on the composition of assets in the majority of large pension funds. The funds continue to rely on the "traditional" assets of government and high-quality corporate bonds (50-55 percent) and publicly traded equities (20-25 percent) of all pension fund assets. In recent years, the funds sought to enhance yields—the so-called 'search for yield'—by investing in commodities, private equity funds, hedge funds, commercial real estate and large infrastructure projects. These “alternative” assets account for about 12-15 percent of total assets under management. However, these alternative investments can and have been very volatile, e.g. commodities, and some of the large funds have dropped that category from their investment basket.

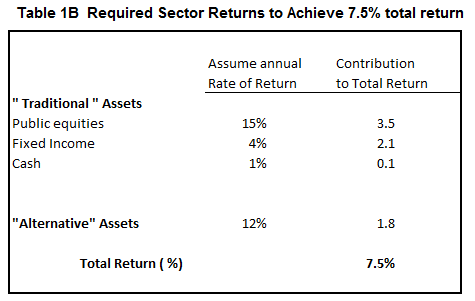

Table 1B considers what the growth rates of the various asset classes need to be in order to generate an overall growth rate of 7.5 percent. Clearly, all asset classes must grow at quite high rates in order to reach the overall target. Equities need to average a growth rate of 15 percent annually, bonds need to return 4 percent a year, and, more importantly, alternative asset classes have to clock in at rates of 12 percent a year to help achieve the overall investment target.

The most important asset class—US Treasuries—has suffered the most as illustrated in Chart 4. As yields in Treasury yields continue to fall since 2011, the spread between Treasuries and target returns has widened. This puts additional pressure on fund managers to seek higher yields in the non-traditional asset groups, especially in commodities and hedge fund activities&mdasg;both of which are very volatile and risky. All the while, the funds cannot run afoul of the regulatory authorities who have to safeguard current and future retirees' income.

Pension fund managers are caught between a rock and hard place. Many US state plans are forced to meet the underfunding issue by increasingly relying on tax receipts to top up funds at the expense of other basic state obligations such as public education. With each passing year, the shortfalls increase, yet the state needs for other obligations continue to climb. Thus the shortfalls come at a considerable cost to the nation.

Some public funds, such as the Canadian Pension Plan, have invested in long-term infrastructure projects at home and abroad as a means of boosting returns. Such opportunities are far and few between. In the US, many pension plans have invested in hedge funds and a variety of financial derivatives as a way to overcome low yields from traditional assets. Nonetheless, this search for yield does not move the needle sufficiently to allow the pension funds to meet their targets.

Check out Kotlikoff: America "Dead Broke" - 9 Trillion in the Red

By no means is this situation confined to the US. The British pension industry has been underfunded for some time, and the situation became a whole lot worse following the Brexit vote. UK interest rates fell significantly since the June vote, applying more pressure on managers to correct underfunding. Finally, the wave of negative interest rates in Germany and other EU countries have made pension managers` lives a lot more difficult in their search for positive-returning assets.

What Does the Future Have in Store for Pension Funds?

The OECD study does not mince words. It states “to reduce insolvency risks, insurers may need to offer lower guaranteed returns on new contracts to reduce liabilities and, in extreme cases, renegotiate current terms. Pension plan sponsors could adjust or terminate existing plans and offer less attractive terms to new employees. Defined benefit pension plan sponsors could increase contributions to funds. Regulators and policymakers will need to remain vigilant to prevent excessive “search for yield”. (1)

Implicit in this report is the recognition that slow global income growth and low-interest rates will dominate the international community and historic investment targets are not expected to be repeated. Thus, we can anticipate a number of changes in the industry, including the demise of the defined benefit program; younger members having to pony up more in pension contributions; taxpayers topping upstate plans; a continual re-assessment of longevity risks; and a downward adjustment to overall investment targets. These changes amount to a significant adjustment to the parameters that guide pension funds going forward.

(1) OECD, Pension Market in Focus, 2015