Originally posted at Briefing.com.

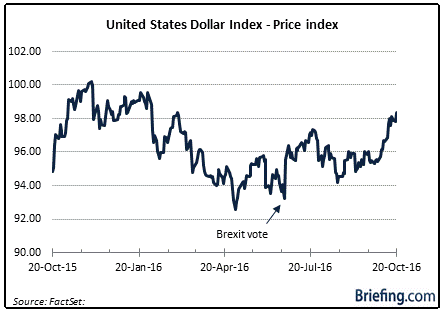

The US Dollar Index includes six component currencies. It's a six-pack with some added kick to it these days, too, seeing how the US Dollar Index has been surging since early October and is trading at eight-month highs.

A guide provided by ICE Futures US states that the US Dollar Index is a geometrically-averaged calculation of six currencies weighted against the US dollar (aka "greenback"). Those six currencies are the euro, the Japanese yen, the British pound, the Canadian dollar, the Swedish krona, and the Swiss franc.

By far, the currency with the most influence on the basket is the euro, which carries a 57.6% weight. The next biggest influence is the yen, which has only a 13.6% weight, and then it's the British pound with an 11.9% weight. To make matters complete, the Canadian dollar has a 9.1% weight, the Swedish krona has a 4.2% weight, and the Swiss franc brings up the rear with a 3.6% weight.

Listen to Eric Hadik on Cycles, Gold, and Stock Market

With these weightings in mind, it makes sense why the US Dollar Index has been surging lately. Two of its most heavily-weighted components—the euro and the British pound—have been tanking. The yen for its part has moved in less dramatic fashion, yet it has been fading and that has also helped boost the US Dollar Index.

This is a matter of some consequence because the residual strength in the greenback isn't associated so much with true economic strength in the US as it is with relative strength, safe-haven flows, and a policy-rate differential trade. In other words, it might be creating more problems than solutions for the global economy.

Seeing Double

There isn't a lot of mystery behind the weakness in the British pound. The Brexit vote has crushed the pound, as investors are envisioning a weaker UK economy in the long run due to a potential loss of single market access to the European Union.

Those concerns have grown more pronounced lately, with chatter from EU officials suggesting the UK should put to rest any notion that it will be able to negotiate a "soft Brexit" whereby it calls its own shots on immigration policy and maintains single market access. The narrative today leans more in favor of a "hard Brexit" whereby the EU enforces a complete divorce with the UK.

Read The Specter of a Hard Brexit

Those divorce papers won't be served anytime soon, yet British Prime Minister May has confirmed that Article 50, which gets the ball rolling on any separation agreement, will be invoked by the end of March 2017. Coincidentally, that's around the same time the ECB's asset purchase program will end, unless the ECB determines it is not seeing a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation consistent with its inflation aim, which, in that case, the program will be extended.

The British pound is sinking—and it has done so at a fairly rapid pace since the Brexit vote and since the Bank of England cut its bank rate to a record low of 0.25%, expanded its purchase of UK government bonds, and introduced a corporate bond buying scheme in early August following the Brexit vote.

The reasons for the euro's decline are a little less clear-cut but generally understandable.

We say less clear cut because the ECB hasn't introduced any more stimulus since the Brexit vote other than to say it could possibly extend its asset purchase program past March 2017. It has provided the requisite guarantee that it will do more if necessary, but holding the line on policy should have been euro-supportive in the sense that it was thought more policy accommodation was likely to follow the Brexit vote.

It was supportive for a time, yet the last few weeks have seen a noticeable breakdown in the euro to seven-month lows. That breakdown, we think, has been precipitated by the following factors:

- A breach of the 200-day moving average at 1.1178 on October 10, which invited increased technical (and momentum-based) selling interest

- The ECB, ironically, holding its policy line as investors worry growth will disappoint without increased policy accommodation now, thereby ultimately necessitating further policy stimulus in the future

- Holding the line on policy now, at a time when the Federal Reserve sounds increasingly likely to raise the fed funds rate before the end of the year, is triggering some capital flight to the US dollar

- Festering concerns about the European banking system, highlighted by troubles among the Italian banks and talk that Deutsche Bank may need to raise more capital (and wouldn't be getting government support if it came to that)

- Uncertainty surrounding the Brexit issue

- Building political angst in front of key elections in the eurozone in 2017 (Germany being chief among them)

Dollar Dynamics

What's going on with the euro is a really important dynamic since the euro has an outsized influence on the movement of the US Dollar Index. To that end, the charts below show that the trough in the US Dollar Index this year coincided with the peak in the euro.

Continued weakness in the euro will translate into continued strength in the greenback.

The benefit of a stronger dollar is that it lowers the cost of imported goods for US consumers. It also helps hold down dollar-denominated commodity prices, namely oil, which should presumably help boost the level of discretionary spending for US consumers, assuming they elect to spend any savings they get from lower energy costs.

Still, a stronger dollar has adverse effects, too.

- It makes exported goods more expensive for foreign buyers, leaving US exporters at a competitive disadvantage

- It weighs on the earnings prospects of US multinational companies

- It makes it more expensive for emerging market economies to repay dollar-denominated debt; and it also weighs on the prices of commodities, which can be key to the economic fortunes for some emerging market economies

- It creates increased price competition from cheaper foreign goods, which can rob US companies of pricing power and can lead consumers to defer spending on the belief an item can be purchased for a lower price at a later date

- It holds down inflation, which can keep the Fed from raising rates. That, in turn, can keep savings rates from going up, which, ironically, drives more savings activity on the part of income earners anxious about their ability to meet retirement goals and having money set aside to deal with any emergency situations like a job loss.

- It can complicate monetary policy decisions at this juncture, as policymakers remain cognizant that higher rates in the US could encourage increased capital flight from foreign economies

The dirty little secret the ECB and Bank of England won't openly admit to—nor the Bank of Japan for that matter—is that they are just fine with their respective currencies continuing to weaken. They are all angling to jumpstart economic growth and inflation, and a weak currency helps in that pursuit.

The Federal Reserve, of course, is hoping to do the same and a rapidly appreciating dollar is not helping wholeheartedly in that effort.

What It All Means

It is often said by US government officials that a strong dollar is in the best interests of the US It is, yet timing matters there.

It is in the best interests of the US when the US economy is strong. When the economy is muddling along, as it is now, and the global economy is doing the same, a strong dollar acts as a break on the drive to achieve escape velocity in the world's largest economy.

It's just one more reason the Federal Reserve is in a real pinch right now. The US economy isn't strong, yet it is strong enough not to have the policy rate as close as it is to the zero bound.

Raising the fed funds rate would presumably be dollar supportive, particularly if other central banks stand pat in a self-serving way. We think the Fed should raise the fed funds rate again relatively soon, but there will be consequences for doing so. A stronger dollar and lower than expected earnings growth would likely be among them.

That comes with the territory, though, for a central bank that badly needs to extricate itself from a monetary policy that doesn't match this non-emergency time.